Jörg Boner

Infusing elegance

What is Jörg Boner’s approach to design?

I believe my approach is shaped like this: I always want to recognize and define the conditions that arise and converge around a project or a commission, the conditions that define a project. This step is essential for me. It’s not about a personal style that is visible from the outside. Instead, these principles or approaches form a base that remains consistent but can take a different shape from project to project, depending on the character and conditions of each project.

Sometimes the constraints come from production conditions, sometimes from price, and we must work economically. The challenge lies in achieving something without losing the beauty or attractiveness of the object. This balance interests me deeply: how to meet economic conditions while retaining beauty and elegance, or, more precisely, attractiveness.

Beauty, as much as it can be grasped, has always interested me. I think it’s one of the main pillars when it comes to aesthetics. Perhaps we should speak more about aesthetics than beauty. My preferred term, however, is elegance. This word carries a certain grandeur, a visual character. For me, it is a fundamental principle.

Other conditions come into play: the machine that will produce the object, the production conditions, the price, the costs, the possibilities, the timelines, and perhaps the market—although the market itself... of course, the market interests me to some extent since we depend on it. Still, I find it challenging to visualize the market."

How do you define your design process?

The conditions drive the creative process. Initially, we must grasp the framework of a project, and it is within this framework that we start—with no idea, image, or concept. First, we must understand the nature of the commission, then lay one stone after another.

Production conditions define the process and serve as the starting point. Once these are identified, we can proceed step by step. My personal interests then come to the forefront, such as visual quality, beauty, and elegance.

Sometimes, however, production constraints are accepted, and we may even try to optimize them. This aspect is also crucial: questioning how we intend to produce the object, understanding if the technique is justified, or exploring whether there could be another way to proceed.

What value do paper models have in your process?

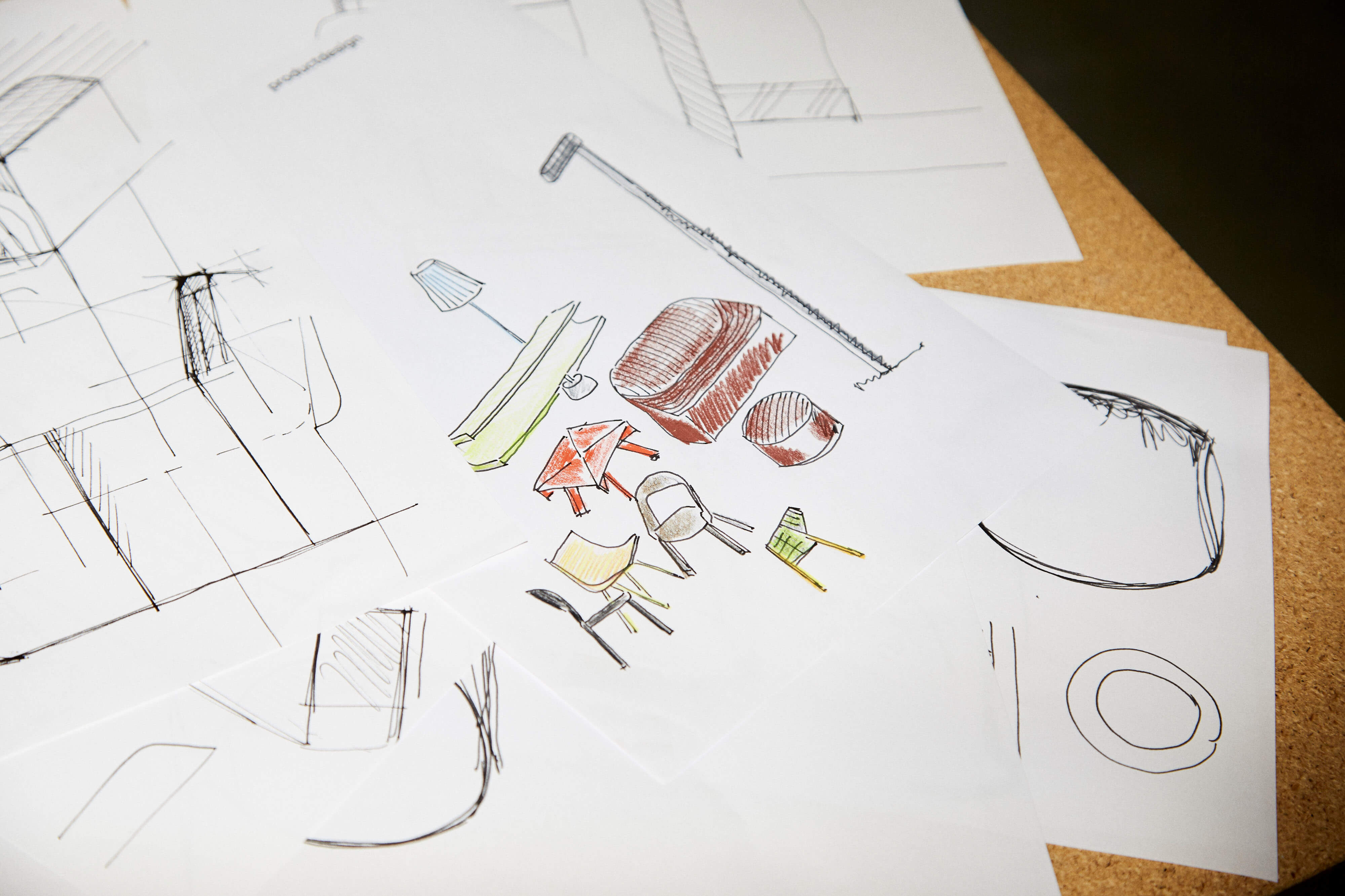

They are an extremely important step. Sketching is not necessarily critical in my case, but the first model is a crucial element. It makes the thought process visible through a realization process.

The cardboard or paper models we construct are, for example, very precise, faithful to the initial 3D sketches. All the forms we imagined on paper will be faithfully rendered, and the object then appears.

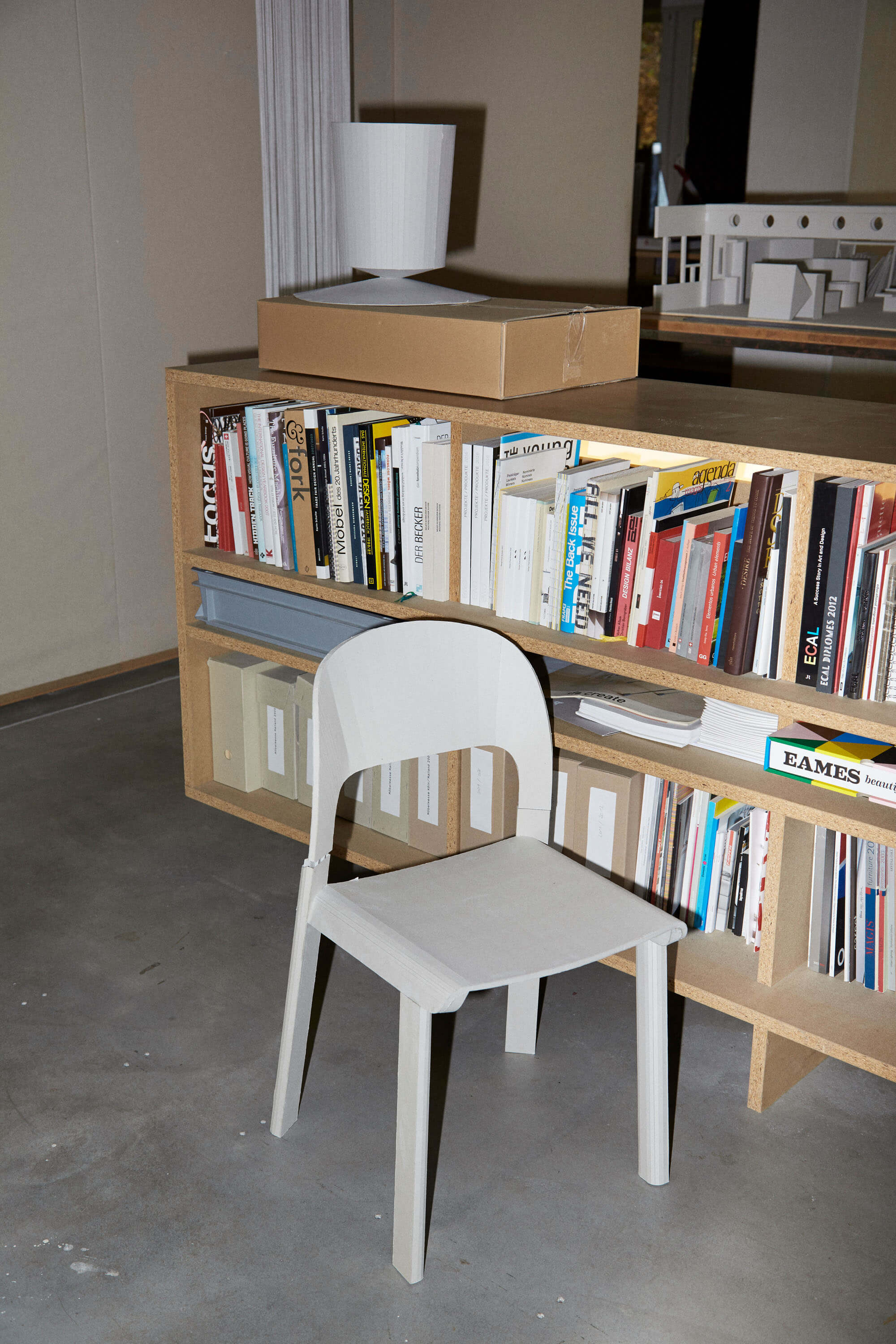

For instance, with a chair, the paper model physically brings it to life, but the object is not yet fully realized. The model occupies an in-between space, a gray area between the idea and the finished product. This phase fascinates me because it marks the moment when an idea transitions into reality.

Are your objects trying to tell a story?

This is a common metaphor in design. I’m not certain how much I buy into it. There are objects that tell many stories, but these narratives don’t interest me that much. I believe more in the idea of 'character.' It’s like with people: you can imbue a product with a captivating character without necessarily constructing a story around it.

You perceive or sense something about it—a quality or a presence that isn’t always visible but can be felt. That’s what I aim for, rather than focusing on storytelling. For me, an object’s primary role is to serve. A chair's role is to be a chair. The interaction between a person and the chair—that’s what interests me. If the chair itself tells too many stories, it disrupts this interaction.

What’s the importance of the user in your design practice?

Usage is very important, and I take it seriously. I am often the first user of the object. While this may be unique, it allows me to draw general conclusions. I rarely envision the client concretely. To me, they are almost like ghosts—impossible to transfer into reality. But we can take inspiration from humanity as a whole, using myself or others in the studio as references.

What’s the difference between industrial and product design for you?

There are differences. Industrial design emerged perhaps in the 1970s, 80s, or 90s, tied to mass production and industries manufacturing identical products on a large scale. This is the classic image of industrial design.

Product design encompasses a broader field, including industrial objects as well as unique pieces or gallery objects. I feel more at home in this interplay between industrial products and unique creations.

Is ‘less is more’ still relevant?

‘Less is more’ is a completely overused concept for me. It has been distorted by marketing. Initially, it was full of meaning, but overuse has stripped it of its substance.

Today, simplicity is often emphasized, and I also value a product that feels simple—not simplistic. The difference is significant. Simplicity is about reduction to the essential, but the essential must retain complexity to hold my interest.

What is the central goal in your practice?

My central concern is to infuse elegance into an object. Elegance is a word that resonates with me because it encompasses multiple facets—not just beauty or functionality but a combination of remarkable attributes. If it were a person, it would be someone you fall in love with.

Interview by Profiler / Photography by Douglas Mandry