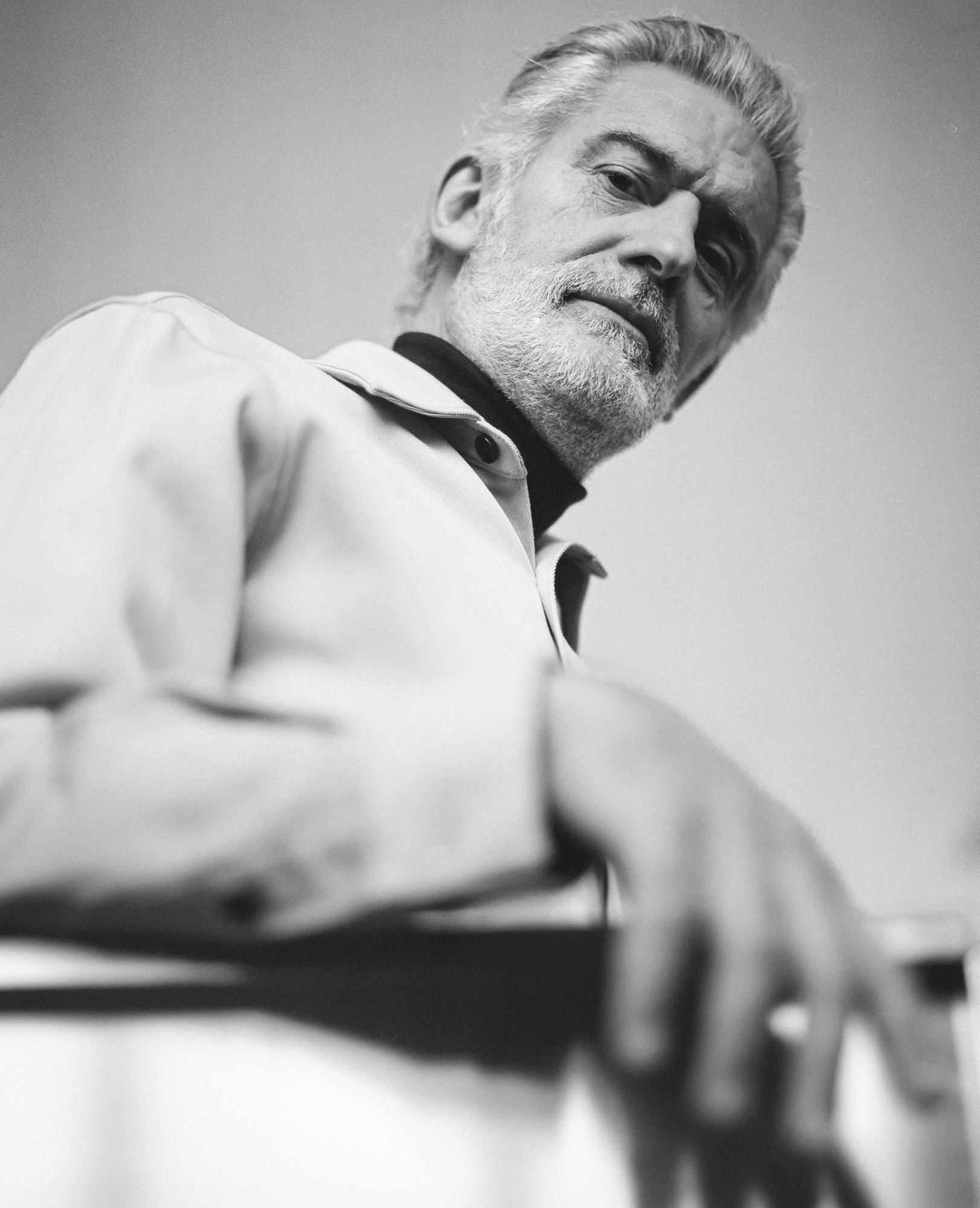

Alfredo Häberli & Iittala

20 years of design

The Argentinean-born, renowned Swiss contemporary industrial designer Alfredo Häberli has collaborated with Iittala already since 1999, for a bit over two decades. During that time, Häberli has created numerous designs for Iittala, which have generated new paths and directions for Iittala as well as the social situations for which the designs have been created.

Häberli's designs have become some of Iittala’s best-known, most beloved, most distinctive and award-winning collections. The designer is known, among other things, as the creator of such internationally acclaimed collections of Iittala, as Essence (2001), Origo (1999) and Kids’ Stuff (2003).

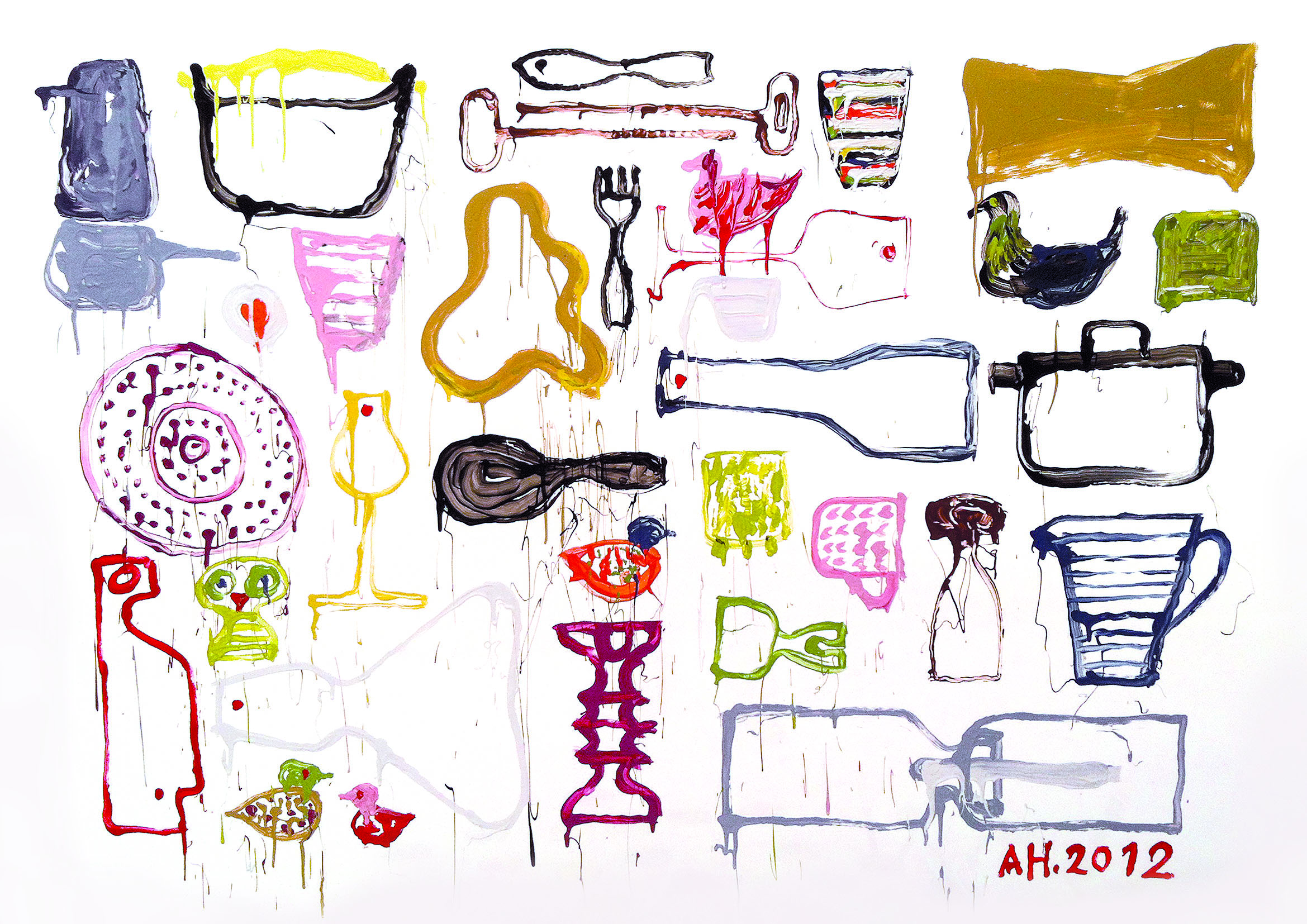

The exhibition Memories of the Future showcases over two decades of collaboration between Häberli and Iittala, featuring a curated selection of objects and sketches from Häberli's personal archive and Iittala's collections. Complemented by video footage filmed in his Zürich studio and an exhibition booklet, the display offers an intimate glimpse into Häberli’s personal experiences, insights, and the design processes behind each project.

“Having a reason to dig into my archive and to reminisce about the joint history with Iittala, fills me with joy. I found ideas, sketches, prototypes and out of production items, and items that have been produced since the beginning of our collaboration.”

In the exhibition the objects of different projects are arranged in a large display where they can be viewed as their own entities and at the same time interacting with each other, creating multiple layers and background for what is ultimately realized, for example, as a glass or a bowl in people’s daily lives and celebrations.

“I am deeply honoured to be able to work with a brand like Iittala, with such a rich history. Together we have managed to create some products that could be considered iconic – some have survived turbulent times for the industry while others have tested the accumulated knowledge and visionary views from all involved individuals", Häberli says.”

If you weren’t a designer, what would you do?

If I wouldn’t be a designer, my profession would probably be between cartoonist and engineer. The approaches in these two professions are similar, roughly comparable to my current profession: to achieve a lot with little resources. I call it economy of means—whether in drawing, building or designing.

Can you describe your design process?

When I am asked for a project, many different images appear in my mind’s eye when approaching a new topic: associations, references, colours, sometimes they are specific objects but also abstract feelings. I allow all these attempts, for the beginning without judging and just observe from a distance. I refer to this step as “Inclusion”. Then I add more images to the collection, also producing sketches and trying to order and discover similarities, with the aim of finding themes that repeat themselves. I call this phase “Limiting”. When I am ready, I choose a project manager in my studio who, whenever possible, supervises the project from start to finish. I myself oversee the project very closely through all the subsequent steps—and together as a team we also decide on what happens next. It is like a game of ping-pong between us.

How do your Swiss and Argentinean cultures mix?

When I was a child, my parents run a successful restaurant in Argentina. So, dining culture has always been something very familiar to me. Also, when we started our cooperation with Iittala, I had already produced various designs for restaurants and bars. This, and my different approach to the Scandinavian way of living, was certainly an added value. My taste as a Swiss designer suited the Scandinavian way of living quite well. My very open personality was appreciated, even if I sometimes I said things that people would rather not hear. My philosophy is honesty, coherence and loyalty.

What happened when you first introduced Origo?

Immediately after I first presented the collection, I was asked what the patterned version would look like. As a very young designer, you feel somehow under attack by questions of this kind. For me, the white ceramic pieces were beautiful enough in themselves and I could not conceive of a floral pattern. On the flight back to Zürich, I was somewhat irritated by the question about decoration and I thought about doing a rainbow with all the colours in it. I designed coloured stripes of irregular widths and applied them only to the smallest cup.

We sold the entire year’s production in the first few weeks. Origo became a bestseller and made me very famous in Scandinavia. Because of its success, the striped design was put on all the cups—and I realised for the first time in my life what it meant to receive royalties. That was my start with Iittala in 1999.

What was the starting point to Kids’ Stuff? How do you see designing for children differs from designing for adults?

When I received the commission for this project, our son Luc was just two years old and I was able to observe exactly what everyone experienced in everyday life and at the table—I discovered amazing things. So much was obvious, clear and visible that this project became one of my favourites of the last 30 years.

Children are highly intelligent little creatures. They want to be grown up like the adults and to be treated as such. Just like you should talk with them normally, at eye level, I believe you should also give kids the possibility to handle things easily. They should not have to be frustrated by not being able to get any peas onto a spoon. Designing for children is not about making a piece of cutlery 20% smaller or gluing a cartoon figure on the handle. Children want to use glasses and plates just like ours.

To this day, the press conference remains the most emotional event of its kind I have ever experienced. At Iittala’s headquarters, a kindergarten class was invited to use Kids’Stuff as inspiration for a wide variety of creative activities. This resulted in decorative pieces, performances, poems, and, most beautifully of all, a song played on a traditional Finnish instrument. The media attendees had tears in their eyes—they must have been young parents, just like me.

How would you describe the Finnish food culture at the time of the launch of Essence? And how did you approach the design brief?

Essence arrived at an important moment in Finnish food culture. Dining habits had started changing: outdoor dining became more elegant, the first Finnish restaurants were receiving stars, and people became wine lovers. Iittala was catching up with this shift. Until then, most of the wine glasses in the catalogue had all had sturdy stems. Take Wirkkala’s Tavastia or Tapio series, or Kekkerit and Jurmo by Timo Sarpaneva. Before those—we are talking about 20 years ago—Finns tended to use beer glasses or water tumblers for wine drinking, if they drank wine at all.

With this background in mind, we again asked the question: what is the minimum number of items needed on a modern dinner table while still being able to serve a full range of wines? The idea for the glass range was to create a balance between tradition and modernity, between celebration and daily use, a balance with one and different uses. In a way, I tried to find the essence in-between. Formally, I wanted a more masculine shape, so that Essence could differentiate itself from the wine glass’ traditional female form. The stem base is identical for all glasses in this range and the bowls have their unique characteristic shape.

Back in 2001, the engineers at the glass factory saw me as fairly young and naïve. They asked me, “Alfredo, is this the first time you’ve designed in glass?” Proudly and cluelessly I answered yes, which was received with plenty of eye rolling. I was told that the design would be impossible to produce! That was a real downer. However, the technicians and engineers accepted the challenge. The only solution was to work with pressed glass and develop a new material, one that’d be particularly hard and durable… and there you had it: an invisible invention.

You are quite a collector, what makes you pick up an object and keep it? How do you build your collages?

I could tell a story for every object in the studio or at home. Every object has an aspect that interests me. I try to synthesise the hidden intelligence, the fascination or the questions that it triggers in me into something new, or to make something different from it.

There’s a lot of discussion about the “future of design” and at the same time people love the classics and history. In your own work for Iittala, how would you see your relationship in balancing between tradition and innovation?

I see my contribution as a designer as continuing to write the history of design. Upcoming designs should take existing ones into account. Innovation is the motivation to make something new, in whatever way. With the Essence glasses, it was a new type of material that made its shape possible. With the Origo tableware it was the reduced number of pieces and the way the individual vessels could be fixed to the saucers.

What makes an icon? How does one design a classic?

Whether a product becomes an icon is only determined over time. My designs were never intended to be fashionable, but are made today and intended for tomorrow.

Creative Direction by Sebastian Vargas / Photography by Justine Stella Knuchel / Interview Päivi Niemi @ IITTALA